Looking back through the past six decades, many milestones in aviation can be identified. From the invention of the jet engine to the introduction of the Airbus A380 superjumbo, each of these milestones holds its rightful position in the pages of aviation’s history books. Scanning back over the individual years, though, one in particular leaps from those pages more than any other: 1969.

55 years ago, in February of that year, the world watched in wonder as the Boeing 747, the largest airliner ever to have been produced by that stage, took to the air for the first time. The aircraft would bring cheaper mass air travel to significantly more people globally than any previous commercial aircraft.

A little under a month later, the world watched on again as an aircraft shaped like a sleek white dart roared into the skies over Toulouse, France, as the first prototype Concorde took its maiden flight. Concorde would introduce the world to the concept of commercial supersonic travel, in a show of formidable and inspiring engineering excellence.

With two major aviation firsts already achieved that year, the triumphant trilogy of 1969 was completed in July as almost 650 million people worldwide watched three American astronauts fly to and successfully land on the Moon’s surface – an event of such magnitude that its repercussions are still impacting our everyday lives.

So, strap in as AeroTime revisits the aviation landmark year of 1969 – a year that changed how we would travel by air forever.

February 9, 1969 – The first flight of the Boeing 747

The legendary Boeing 747 was the brainchild of two visionaries in American aviation – Joe Sutter, who led the aircraft’s design team at Boeing, and Juan Trippe, the then charismatic head of Pan American World Airways (Pan Am).

With the demand for air travel rapidly increasing throughout the 1960s since the dawn of the jet age, aircraft manufacturers such as Boeing, Douglas, and others had worked hard to produce larger aircraft to keep up with demand. Types such as the Boeing 707 and Douglas DC-8 had transformed intercontinental travel by lowering the cost per seat for airlines, and consequently airfares for passengers.

It was during this boom for international travel that Juan Trippe approached Boeing, asking whether the company could design and build an airliner 2.5 times larger than the 707, for which Pan Am had been the launch customer. The new aircraft would have to offer a 30% lower seat cost per passenger over the 707, while being able to fly further and carry more passengers on the key international routes of the era, such as New York to London.

With the 747 already on the design board (thanks to a previous US military request for proposals for a larger jet-powered cargo aircraft), Sutter and his team took that existing design and repurposed it as a commercial airplane, capable of carrying up to 500 passengers, plus belly cargo, on routes of 8-9 hours flying time. In April 1966, with the 747 final design work complete, Pan Am placed an initial order for 25 of the ‘jumbo jets’ from Boeing, in a $525 million deal that would enable production of the new aircraft to begin.

The first 747, registered N7470 and given the apt name of ‘City of Everett’ (after Boeing’s then-hometown in Washington state), rolled out of the factory at Everett’s Paine Field near Seattle on September 30, 1968. Gathered for this momentous event was the world’s press, alongside representatives of the 26 airlines that had ordered 747s by that point.

But while the aircraft was complete, various ground tests were required to satisfy the Federal Aviation Administration sufficiently for them to grant a permit for the first flight.

On the morning of February 9, 1969, N7470 took off for the first time from Paine Field, as hundreds of spectators looked on in awe. In command of the huge aircraft that day was Boeing’s Chief Test Pilot Jack Wardell. He was accompanied on the flight deck of N7470 by Engineering Test Pilot Brien Singleton Wygle and Flight Engineer Jesse Arthur Wallick.

Although the weather on that cold February morning was initially grey and overcast, conditions soon improved, and by 11:20 the aircraft was cleared to begin its very first take-off run and take its maiden flight. Captain Wardell advanced the four throttles and upon reaching a speed of around 165 mph (263kph), the aircraft’s nose was lifted, and the plane headed skyward.

Having safely reached the required test altitude, the crew carried out a range of general handling tests, amongst others required before the FAA could certify the Boeing 747 for commercial passenger service. These tests included a simulated loss of hydraulic power, stall recovery, and other intentional cross-control maneuvers, such as a ‘Dutch Roll’. The four engines were also put through their paces, with the crew ensuring that various adverse attitudes would not restrict fuel flow to the engines, causing them to stall.

With the handling and engine tests complete, the next test involved lowering the flaps in stages to see how the airframe responded to the increased drag. However, upon selecting the flaps down from 25 to 30 degrees, the aircraft shuddered, and a marked vibration ran through the airframe. With the flaps retracted back to the 25-degree setting, Wallick was dispatched from the flight deck to make a visual check of the flaps from the cabin windows downstairs.

Upon his return, Wallick reported that a section of flaps on the right wing had become loose, causing the vibration. Although the test flight was prematurely terminated at this point, the aircraft continued to rendezvous with a Boeing 727 for an aerial photo shoot over Washington for prosperity.

That being accomplished, Wardell brought the larger plane back to Paine Field at 12:50, making a near-perfect landing – quite a feat for such a large aircraft on its first try-out.

Although the Boeing 747’s maiden flight did not pass without issue, it was immediately hailed as a huge success. Not only did it mark the start of mass air travel, but it would also pave the way for over five decades of Boeing 747 production, with the type seeing various upgrades and derivatives over that time.

Production of the 747 finally ended in December 2022 with the 1,574th and final 747 rolling out of the Boeing plant in Everett and being handed over to customer Atlas Air.

March 2, 1969 – Concorde’s first flight

Exactly three weeks after Boeing had grabbed headlines with the first 747 flight, it was the turn of the Europeans to grab the spotlight.

In February 1965, eight years after the UK’s Ministry of Supply had first formed the Supersonic Transport Aircraft Committee (STAC) to examine the feasibility of designing and producing a supersonic airliner, France’s Sud Aviation (later to become part of Aérospatiale) and the UK’s British Aircraft Corporation began the construction of two Concorde prototypes.

The two companies built one aircraft each, at their respective factories in Toulouse (aircraft 001) and Filton, near Bristol, England (aircraft 002).

Following the conclusion of four years of intensive design work, at the start of 1969 Concorde was certified by the French and British aviation authorities to begin test flights. The French-built aircraft 001 would be the first to fly, to be followed by the British-built aircraft just a few weeks later.

So it was that the first flight of a Concorde took place on March 2, 1969, from Toulouse-Blagnac Airport in the southwest of France. Aircraft 001 taxied to the end of Toulouse’s runway, with the world’s media looking on. At the controls was André Édouard Turcat, a former test pilot for the French Air Force who had been hand-picked by Sud Aviation to take their exciting new plane for its first flight.

This first flight had been delayed by two days of inclement weather in Toulouse. However, now in clear skies, the delta-winged Concorde roared and smoked its way above Toulouse. Climbing to 10,000ft (3,080m), the Concorde accelerated to around 300mph (483kph), though remaining well under supersonic speeds for this initial sortie.

Having been airborne for just 27 minutes, the aircraft made a safe first landing back at Toulouse Airport. Captain Turcat subsequently told reporters gathered to witness the occasion that Concorde had behaved as expected, “with no actual issues, except for some minor malfunctions with instruments, which was unavoidable”.

The first British-built Concorde (002) took its first flight from Filton on April 9, 1969, piloted by Captain Brian Trubshaw.

Both prototypes were displayed at the 1969 Paris Airshow, following which aircraft 001 set out on a promotional sales tour to the US during September 1969, which also included the type’s first Atlantic crossing. Meanwhile, 002 headed to the Middle East and the Far East in the hope of drumming up customers there.

The Concorde finally entered service in 1976, although just two airlines would go on to own and operate it during its 27-year career, namely Air France and British Airways.

July 20, 1969 – The first moon landing

Coming towards the end of a momentous six-month period for global aerospace development, the first landing on the lunar surface by a manned space mission (Apollo 11) in July 1969 marked the pinnacle of ingenuity and engineering brilliance. As Neil Armstrong took his first steps on the Moon’s surface, he could scarcely have grasped that his actions would change the world forever.

The American resolve to send astronauts to the Moon had begun in the US Congress in May 1961, when President John F. Kennedy declared, “I believe this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to Earth”.

At the time, the United States was trailing behind the Soviet Union in space development and was keen to forge ahead in that race. In 1966, following five years of work, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) conducted the first unmanned Apollo mission into space, designed to refine the structural integrity and overall design of the proposed launch vehicle and spacecraft combination that would later take humans to the Moon.

NASA pressed ahead, sending the manned Apollo 7 mission around the Earth in October 1968, followed by Apollo 8, which took three astronauts to the far side of the Moon and back in December of the same year. In March 1969, Apollo 9 tested the lunar module for the first time, while remaining in Earth’s orbit. Finally, in May 1969, NASA carried out a ‘dry run’ of a lunar landing mission, sending Apollo 10 around the Moon with three crewmembers onboard.

After almost eight years of perseverance, the stage was finally set for a manned mission to land on the Moon.

At 09:32 EDT on July 16, 1969, Apollo 11 blasted off from Kennedy Space Center, Florida carrying astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins onboard. Armstrong, a 38-year-old civilian research pilot, had been selected as the commander of what would become a truly historic mission.

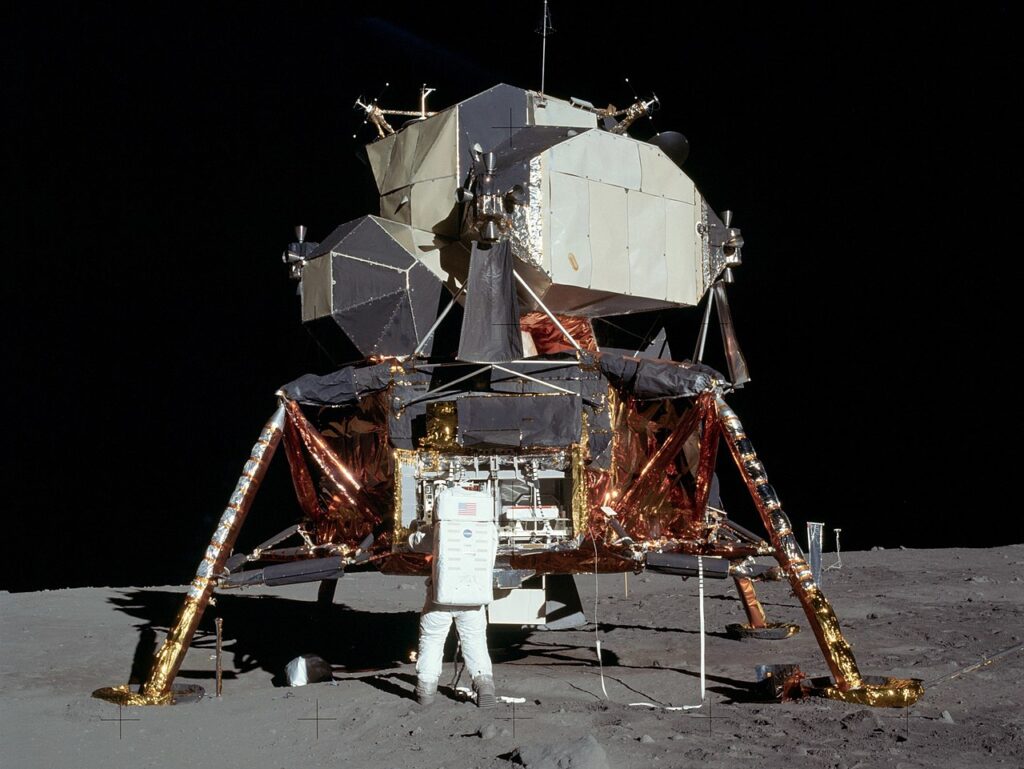

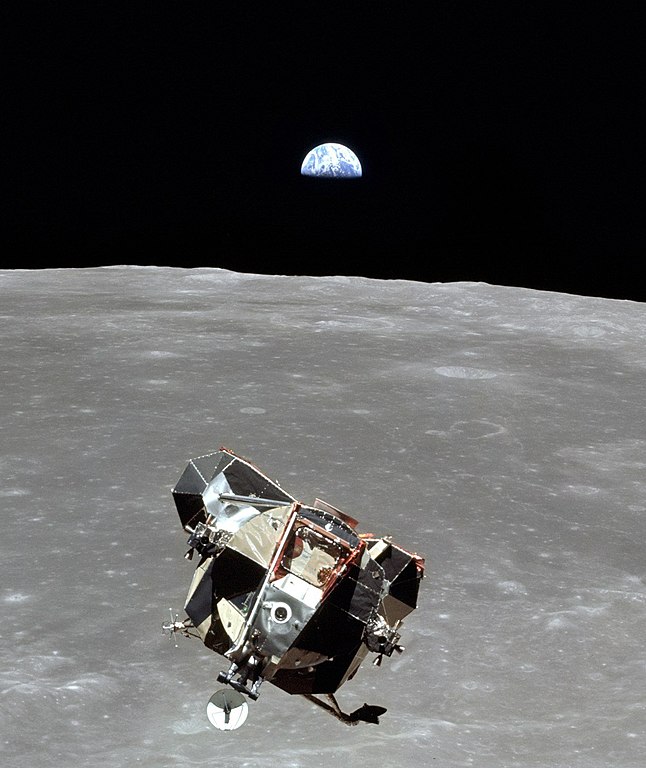

After traveling 240,000 miles over 76 hours of flying time, Apollo 11 entered lunar orbit on July 19, 1969. The following day, at 13:46, the lunar module (callsign ’Eagle’), manned by Armstrong and Aldrin, separated from the command module to begin the descent to the Moon’s surface. Collins remained at the controls in the command module.

At 16:17, the Eagle touched down on the southwestern edge of the Sea of Tranquility. Armstrong immediately radioed to NASA Mission Control in Houston, Texas, the now-legendary message: “The Eagle has landed.”

At 22:39, Armstrong made his way down the module’s ladder. A television camera attached to the exterior of the Eagle recorded his movements, beaming the images back to Earth where an estimated 650 million people worldwide huddled around television screens to watch the remarkable events unfolding in (almost) real-time. At 22:56, Armstrong stepped off the ladder and planted his foot on the Moon’s surface.

19 minutes later, Aldrin joined him on the Moon’s surface and the two men took photographs of the terrain, planted a US flag, and spoke with President Richard Nixon via a radio link patched through Houston mission control.

By 01:11 on July 21, 1969, both astronauts had returned to the lunar module and spent that night sleeping within, while still on the Moon. Around 12 hours later, the Eagle began its ascent back to the command module where the two men rejoined Collins. At 00:56 on July 22, 1969, the crew of Apollo 11 began their journey back to Earth, splashing down in the Pacific Ocean at 12:45 on July 24, 1969.

Independently significant, together world-changing

Taken in isolation, each of these three events was a marvel of engineering, designed and built by some of the most brilliant minds of the day. Independently, each ‘first’ captured the attention of millions and became a significant milestone in the history of aviation. Yet, given that they occurred within six months of each other, the huge collective impact of these three events rippled around the world, shaping how air travel would change and develop over the coming decades.

The 747 brought reduced-price air travel to many, opening up the world of international travel to the masses to a previously unseen degree. The 747 also changed how large aircraft were developed and built, showing airlines and airports the effectiveness and economies of scale offered by large passenger aircraft.

The arrival of the 747 brought design changes at airports, too. With hundreds of passengers arriving and departing on every jumbo jet, airports had to adapt quickly, with expanded boarding lounges, immigration halls, check-in counters, and other terminal facilities – changes that are still in evidence at many international airports today.

Lastly, the 747 raised the bar in terms of passenger comfort, and the groundwork laid down by the ‘Queen of the Skies’ in this arena is still used by aircraft interior designers of the modern age in terms of cabin layouts, facilities onboard, and comfort levels.

Concorde, meanwhile, showed just what could be achieved by aerospace teams collaborating to reach a common goal. For 27 years, the world’s fleet of Concordes crisscrossed the Atlantic Ocean, as well as being seen in many other parts of the world.

The development of the supersonic airliner showed the world that speed matters, and that in an increasingly time-pressured world, there is a market for saving several hours while also using one’s time more productively.

Inspired by this mantra, Concorde’s legacy, and the pervasive allure of speed, present-day companies such as Boom Supersonic are striving to bring a supersonic commercial airliner back to our skies. Should any of these companies succeed, much faster and cheaper air travel could become accessible, opening more markets to new travelers just as the 747 did in its heyday.

While there are many obstacles still to be overcome (many of which contributed to the grounding of the Concorde in 2003), if this can be achieved, then perhaps one day we will once again cross the world’s oceans in just a small handful of hours.

Lastly, regarding the Moon landing, without the work that went into getting humans to land on the Moon’s surface, the aviation world would not enjoy the benefit of a huge range of innovations that were developed by NASA and its partners during the Apollo program.

From fly-by-wire technology, satellite navigation, and advanced flight management and navigation computers to weather radar, satellite-based communications, and the types of meals served on commercial aircraft and even the way they are cooked onboard (e.g. via microwave ovens) – all of these advancements owe a huge debt to the work done for the Apollo missions.

Simply put, airlines of the modern age still rely on technology developed during the 1960s to get us where we want to be in a safe and timely manner.

Conclusion

Without the technological developments and innovations brought about by the Boeing 747, Concorde, and Apollo 11 ‘firsts’, modern air travel today could be much slower, less reliable, more expensive, and less safe than it is – the benefits of which we can all enjoy, whether it be for leisure or business travel, on a commuter airline or an international megacarrier.

While it may be tempting to think of these innovations as relics from yesteryear, or developments from another age from which the world has moved on, you might want to think again.

As you traverse the continents from the comfort of your modern airline seat, watching the inflight entertainment or sending messages via the onboard Wi-Fi to loved ones, you might even reconsider the huge significance of those historic leaps forward during 1969.

In what other ways do you think these three events changed the way we travel by air today? Let us know your thoughts in the comments section below.